Thocmentony (later Sarah) Winnemucca: The First Native American Woman to Write an Autobiography

by Gudrun Hutchins

Sarah Winnemucca was named Thocmentony (meaning shell flower) at birth. The statue pictured above shows her holding a shell flower. Later, she used the name Sarah because it was easier for her English-speaking employers to pronounce and spell. (I will do the same in this article.) She was born into an important family of the Northern Paiute tribe in 1844, on the brink of a period of tremendous change for her people. Her mother Tuboitonie was the daughter of the ruling chief. Her father Winnemucca was a Shoshone who had joined the Paiute tribe through marriage. According to her autobiography, she had two older brothers, Natchez and Lee, an older sister Mary and a younger sister Elma.

Gold was discovered in California soon after her birth, causing large numbers of white settlers and adventurers to travel through her people’s homelands in Nevada to California. The Paiute Nation (spelled Piute by Winnemucca) was a loosely organized tribe of itinerant hunter-gatherers. They had not developed a warrior culture like some of the Tribal Nations of the plains or a pueblo culture like the tribes of the Southwest. They also did not grow any crops. Men fished the lakes and rivers and dried the fish for sustenance in the harsh winter. They hunted rabbits, deer, mountain sheep, and antelopes and also dried some of the meat to preserve it. Paiute women collected seeds (primarily pine nuts) which they ground into a meal with hand-held stones. Women also dug roots and collected plants as part of the food supply. When the tribe was threatened, they would disappear into the mountains for a period of time.

Contact with white civilization changed the tribe forever and the Winnemucca family played a significant role in shaping that contact. Sarah’s grandfather counseled his tribe to accommodate the white settlers and soldiers, believing that it would be to the benefit of both peoples to practice peace.

In her own words from her book:

“I was born somewhere near 1844, but am not sure of the precise time. I was a very small child when the first white people came to our country. They came like a lion, yes, like a roaring lion, and have continued so ever since, and I have never forgotten their first coming. My people were scattered at that time over nearly half of all the territory now known as Nevada. My grandfather was chief of the entire Piute nation, and was camped near Humboldt Lake with a small portion of his tribe. When the news was brought to my grandfather, he asked what they looked like. When told that they had hair on their faces and were white, he jumped up and clasped his hands together and cried aloud, “My white brothers, — my long awaited white brothers have come at last!”

“He immediately gathered some of his leading men, and went to the place where the party had gone into camp. Arriving near them, he was commanded to halt in a manner that was readily understood without an interpreter. Grandpa at once made signs of friendship by throwing down his robe and throwing up his arms to show them he had no weapons; but in vain, — they kept him at a distance.”

During the next years larger numbers of white settlers moved through the Paiute lands. Captain (later General) Freemont met the Paiute Chief; the two liked each other and became good friends. Freeman named the Paiute Chief “Truckee” meaning “good” or “very well” in the Paiute language and the name stuck. He also named the Truckee River after him in his maps. Winnemucca’s grandfather assisted Freemont with a mapping project and followed him to California with twelve of his people to fight Mexican influence there. When Sarah’s grandfather returned he told the Paiutes what a beautiful country California was. He spoke to them in the English language which was very strange to them all. He and his men brought back guns and military uniforms with many brass buttons that impressed their people.

“My people were very much astonished to see the clothes, and all that time they were peaceable toward their white brothers. They had learned to love them, and they hoped that more of them would come. Then my people were less barbarous than they are nowadays.”

“That same fall, after my grandfather came home, he told my father to take charge of his people and hold the tribe, as he was going back to California with as many of his people as he could get to go with him…. That same fall, very late, the emigrants kept coming. They could not get over the mountains, so they had to live with us. It was on the Carson River, where the great Carson City stands now. You call my people blood seeking. My people did not seek to kill them, nor did they steal their horses, — no, no, far from it. During the winter my people helped them. They gave them such as they had to eat. They did not hold out their hands and say:

You can’t have anything to eat unless you pay me. No, no such word was used by us savages at that time; and the persons I am speaking of are living yet; they could speak for us if they chose to do so.”

As more whites moved west, however, the Paiutes heard horror stories about the killing of Indians. They apparently also heard a garbled account about the Donner Party, some of whom survived a winter trapped in the Sierra Nevadas by eating their dead. These stories terrified Sarah. Her fears were intensified by an experience she describes in her book. One morning, hearing that white men were coming, a tribal group fled in terror. Sarah’s mother, who was carrying a baby on her back and pulling Sarah by the hand, found that she couldn’t keep up. She and a relative decided to hide their older children by partially burying them in the ground and arranging branches to shade their faces. “Oh, can anyone imagine my feelings,” Sarah writes, “buried alive, thinking every minute that I was to be unburied and eaten up by the people that my grandfather loved so much?”

At nightfall, the mothers returned and dug up the girls. It was an experience Winnemucca never forgot. It was several years before she would look at white people or forgive her grandfather for his love of them. After seeing that white men had set fire to the tribe’s stores of food and that all their winter supply was gone, Sarah’s father, Chief Winnemucca could no longer agree with his father-in-law that the white men were his “brothers.” The children continued to be afraid of the “owls” – white men with white (light blue) eyes and hair (beards) on their faces.

When Sarah was six, her grandfather took a tribal group including his daughter and her children on a trip to an area near Stockton, California. The men, including Sarah’s bothers worked in the cattle industry and were well paid in money and horses. Sarah’s mother and her daughters stayed in the home of one of the men that her grandfather had befriended on an earlier trip and helped with some of the domestic work. Sarah was afraid of the white men, but liked the luxuries in the houses.

The Paiute families saw many wondrous things during this California trip including “a house that ran on water without sinking” and had a very loud whistle and sweet sounding bell. They also saw and lived in some very large houses with stairways that led to upper floors. The children and some of the women had an opportunity to travel in a house on wheels (covered wagon).

Meanwhile, the Paiutes started to die from the diseases that the white settlers had brought with them. They were convinced that the water in the rivers had been poisoned by the white settlers. Sarah also became very ill and her face was so swollen that she could no longer see well. Her illness was due to poison oak and a white woman came daily to put medicine on her face. Sarah thought that the woman was a white angel and asked her mother whether she had wings.

The chapter of Sarah’s book, entitled “Domestic and Social Moralities,” details some of the customs of Paiute families and the rituals of the tribe for the courtship of young men and women before marriage. Many of the girls were named after flowers and had their own “flower song” which they sang during a spring festival as they participated in group dances with potential suitors. After a girl grew into womanhood, her grandmother became her special guardian to make sure there was no sexual contact before marriage. The girl even slept beside her grandmother at night. A young man interested in marrying her would sit fully clothed at her feet throughout the night, and possibly many nights in a row. Young men were considered “of age” after they were strong enough to use a large bow and kill a large animal.

She also writes about the rituals of an antelope hunt during which the antelopes were “charmed” before they were hunted. This “charming” ritual took place for several days and involved singing and a special drum used by the chief for only this purpose. It required both women and men as participants.

During council meetings, men sat in a circle. The women sat in an outer circle around them because there was too much smoke in the center where the men were always smoking. The women were allowed to speak and everyone listened to what they had to say.

All of the Paiute women had long hair that typically extended below their waist. If a Paiute husband died, part of the mourning ritual required that his widow cut off her hair, braided it, and placed it on his chest. She would then be in mourning until her hair grew back to the original length and her father-in-law gave her permission to remarry. Paiute men also had fairly long hair and cut it off if their wife or another close family member died, but they were not required to be celibate until it grew back to its former length.

In 1857, their grandfather arranged for Sarah (then 13) and her sister Elma to live and work in the household of Major William Ormsby and his wife. The Ormsby’s lived in Genoa, a small town close to Carson City. The girls did domestic work and learned how to sew and cook. They also had an opportunity to improve their English. Sarah apparently learned to read and write English while at the Ormsbys and began to be at ease in going back and forth between Paiute and European-American cultures. She was one of very few Paiute in Nevada who knew how to read and write English; most members of her extended family spoke English.

A large silver lode was discovered in Nevada in 1859 and their father arranged for his daughters Sarah and Elma to be returned to him.

Father of Sarah Winnemucca

Miners now started to settle within the Paiute homelands in Nevada to mine the silver ore, rather than only travel through the territory on the way to California. Open conflict occurred in 1860 after the Paiutes shot and killed two white men who had kidnapped and abused two Paiute girls. The Paiutes inserted Shoshone arrows into the wounds to confuse the issue, but the white settlers did not care about the details. In their view any Indian was a savage and they were all bad.

Settlers and miners organized a militia making Major Ormsby their very reluctant leader. He was killed by the Paiute in a disciplined confrontation. Settlers were alarmed at how well the Paiutes fought and the ill-prepared miners could not hold their own. Sarah’s cousin Egan was the Paiute’s new war chief by then and was called “Young Winnemucca” to differentiate him from Sarah’s father “Old Winnemucca.” Sarah’s grandfather died during October 1860.

In 1861 Nevada was established as its own territory; before it had been part of the much larger Utah territory. In 1864 Nevada became a State. The new governor James Nye frequently acted against Native Americans who were accused of raids and cattle stealing. In 1865 Captain Almond Wells led a Nevada volunteer cavalry across the northern part of the state, attacking Paiute bands. While Sarah and her father were on a trip to another tribal group, Wells and his men attacked Old Winnemucca’s camp, killing 29 of the 30 persons at the site who were old men, women, and children. The chief’s two wives (including Sarah’s mother) and infant son were killed. Although Sarah’s older sister Mary escaped the raid, she died later that winter due to severe conditions.

In 1868 about 490 Paiute survivors moved to a military camp on the Nevada-Oregon border which became known as Fort McDermitt. They sought protection from the US Army against the Nevada volunteers. In 1872 President Ulysses Grant established the Malheur Reservation in eastern Oregon for the Northern Paiute to separate them from the settlers and adventurers seeking to profit from gold and silver. Sarah, her brother Natchez and his family, and their father moved there in 1875.

Sarah married Edward Bartlett, a former Lieutenant in the Army on January 1872 at Salt Lake City, Utah. He abandoned her, and she returned to Camp McDermitt. In 1876, after she had moved to Malheur Reservation, she got a divorce and filed to take back her name of Winnemucca which the court granted.

The Paiutes were extremely fortunate to be assigned Samuel Parish as their first Indian Agent at the Malheur Reservation. Since the Paiutes knew nothing about agriculture, he taught them how to plow some of the land and plant crops. During the first year they raised potatoes, barley, oats, corn, several different vegetables, watermelons, and cut hay for the horses and mules. Some of the men split rails for fences, built a dam, and dug a ditch under his instruction to divert some of the water of a nearby river to irrigate their crops. To feed the Tribe before their crops were harvested he ordered many wagonloads of provisions. He distributed clothing and blankets to the men, some of it was army issue. The women had to wait a little longer until he could provide clothing for them. The second year each woman received 10 yards of calico, four yards of flannel for underwear, and several yards of unbleached muslin. There was great rejoicing as each woman decided what she was going to sew for her children and herself from this allotment of materials.

Parish paid the men $1 per day for their agricultural labor. After the crops were planted, he gave the men one month off to hunt and fish, and issued powder and ammunition to each man. Most of them had arrived with guns.

Parish also encouraged the Paiutes to cut lumber and build a school for their children. After the school was completed, he asked his brother and his wife to join him on the reservation and they were officially appointed to their new positions. Mrs. Parish became the school teacher for over 200 school children with Sarah assisting part of the time. She had brought a small organ and began by teaching her students a number of songs in English. “The windows were thrown open so that the parents could hear the songs that their children were singing while they were learning.” The Paiutes called Agent Samuel Parish their White Father. They called their teacher Mrs. Parrish their White Lily.

Apparently Parrish was not a Christian, and a new government regulation required that all Indian Agents should be devout Christians so that they would provide compassionate care to their charges. The Paiutes begged Parrish to stay, but apparently he had no choice in the matter. The “devout Christian” who followed Parrish was William Rinehart and in her book Sarah reserves her greatest scorn for him. Rinehart was a proponent of extermination-style warfare; he kept the adults under his thumb and punished the children for very minor mistakes. Sarah recounts that Rinehart sold supplies intended for the Paiute people to local whites. He told them that the reservation land belonged to the government and to the big white father in Washington. The crops they raised also belonged to the government and they had to buy it in order to eat, even though he paid them no money for their labor as Parrish had. The Paiutes starved except for what little fish they could catch. Much of the good land on the reservation was illegally taken over by white settlers who paid bribes to Rinehart. Virtually all of the Paiutes left the reservation because they were abused and starving.

From the age of 24 Sarah worked as interpreter, currier and scout for the US military. In addition to being able to speak, read and write English, she also knew three tribal languages. She was highly regarded by the officers she worked for and included several letters of recommendation at the end of her book.

Sarah Winnemucca

It was during the Bannock War in 1878 that she met her greatest challenge. On her way to Washington, D.C., where she hoped to get help for her people, she learned that the Bannock tribe was warring with the whites and that some Paiutes, her father among them, were being held by the Bannocks. On the morning of June 13, she left Camp McDermit for the Bannock camp with two Paiutes, arriving at nightfall of the second day. Wrapped in a blanket, her hair unbraided so she wouldn’t be recognized, she crept into the camp. There she found her father, her brother Lee, and his wife Mattie, among those held captive. They escaped during the night, but were soon pursued by the Bannocks. Sarah and her sister-in-law raced their horses to get help, arriving back at Sheep Ranch at 5:30 on June 15. She had ridden a distance of 223 miles. “It was,” Winnemucca said, “the hardest work I ever did for the army.”

Winnemucca was poorly rewarded for her hard work for the U.S. Army. Both she and Mattie served as scouts during the Bannock War. After the war, the Paiutes were to be returned to Malheur Reservation, but to Sarah’s distress, they were ordered to be taken to Yakima Reservation on the other side of the Columbia River, a distance of about 350 miles. It was winter, and the Paiutes did not have adequate clothing. Many people died during the terrible trip, and others, including Mattie, died soon after.

Over the years the situation worsened. Winnemucca sent messages, complaints and entreaties to anyone she thought might help. She traveled to San Francisco and spoke in great halls, telling of the mistreatment of her people by the Indian agents and by the government. She was labelled “The Princess Sarah” in the San Francisco Chronicle and her lecture was described as “unlike anything ever before heard in the civilized world—eloquent, pathetic, tragical at times; at others her quaint anecdotes, sarcasms and wonderful mimicry surprised the audience again and again into bursts of laughter and rounds of applause.” News of her lectures reached Washington, and in 1880 she was invited to meet with the President. Together with Chief Winnemucca and her brother Natchez, she met with Secretary of the Interior Carl Schurz and, very briefly, with President Rutherford B. Hayes. However, Winnemucca was not allowed to lecture or talk to reporters in Washington, and the small group were given promises that were not kept.

In 1881 General Oliver Howard hired Sarah to teach Shoshone prisoners held at Vancouver Barracks. While there she met and became close to Lieutenant Lewis H. Hopkins, an Indian Department employee. They married that year in San Francisco.

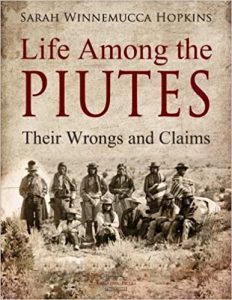

The Hopkinses travelled east in 1883, where Sarah delivered nearly 300 lectures throughout major cities of the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic. Sarah’s cause as taken up by two sympathetic Boston sisters, Elizabeth Peabody and Mary (Peabody) Mann, who had been abolitionists. With their assistance and connections she scheduled a successful lecture tour and in 1883 published her book Life Among the Piutes: Their Wrongs and Claims.

Have any members of the Northern Paiute Tribe Survived?

Yes. Descendants of several different Northern Paiutes Tribes live on the Pyramid Lake Reservation in the center of the original Paiute homeland in Nevada. The reservation includes a large segment of the Truckee River named for Sarah’s grandfather by General Freemont.

Map of Pyramid Lake

The tribe receives a significant part of its income from fishing permits on Pyramid Lake, the home of huge trophy winning cutthroat trout. Visitors may fish the southwestern part of Pyramid Lake where there are also other tourist facilities. The rest of the Lake is reserved for tribal descendants only.

Photo: Janet Davis, Council Chair. Pyramid Lake is in the background

Within the reservation, the tribe has been governed by a council of 10 elders including an occasional woman. A newspaper from Reno, Nevada announced on December 29, 2020 that a woman, Janet Davis, had been elected Council Chair.

She has been a council member for several years and pushed for protecting the tribal residents from COVID-19 by closing the reservation to fishing by tourists. Due to her efforts, the Tribal Health Clinic has received the Moderna vaccine and began vaccinating its seniors in mid-January 2021.

Return to Table of Contents