New York Times Review:

About halfway through “Klara and the Sun,” a woman meeting Klara for the first time blurts out the kind of quiet-part-out-loud line we rely on to get our bearings in a novel by Kazuo Ishiguro. “One never knows how to greet a guest like you,” she says. “After all, are you a guest at all? Or do I treat you like a vacuum cleaner?”

This is Ishiguro’s eighth novel, and Klara, who narrates it, is an Artificial Friend, a humanoid machine — short dark hair; kind eyes; distinguished by her powers of observation — who has come to act as companion for 14-year-old Josie. Like that childhood stalwart Corduroy, she’d been sitting in a store, hoping to be chosen by the right child. AFs aren’t tutors. They’re not babysitters (though they’re sometimes chaperones), nor servants (though they’re expected to take commands). They’re nominally friends, but not equals. “You said you’d never get an AF,” Josie’s friend Rick says, accusingly — which makes Klara the mark of some rite of passage they didn’t want to accede to. Her ostensible purpose is to help get Josie through the lonely and difficult years until college. They are lonely because in Josie’s world, most kids don’t go to school but study at home using “oblongs.” They are difficult because Josie suffers from an unspecified illness, about which her mother projects unspecified guilt.

“Klara and the Sun” takes place in the uncomfortably near future, and banal language is redeployed with sinister portent. Elite workers have been “substituted,” their labor now performed by A.I. Clothing and houses are described as “high-rank.” Privileged children are “lifted,” a process meant to optimize them for success. Readers of Ishiguro’s 2005 novel “Never Let Me Go” will viscerally recall the sense of foreboding all this awakens. If I am being cagey about it, it’s to preserve that effect. But for the inhabitants of the novel, the older generation of whom remember the way things were, these conditions have been normalized, to use the banal language of our own era. Here is Josie’s father, a former engineer: “Honestly? I think the substitutions were the best thing that happened to me. … I really believe they helped me to distinguish what’s important from what isn’t. And where I live now, there are many fine people who feel exactly the same way.” Through Klara, we pick up bits of overheard conversation: a mention of “fascistic leanings” here; a reference to Josie’s mysteriously departed sister there; the woman outside the playhouse who protests Klara’s presence: “First they take the jobs. Now they take the seats at the theater?”

For four decades now, Ishiguro has written eloquently about the balancing act of remembering without succumbing irrevocably to the past. Memory and the accounting of memory, its burdens and its reconciliation, have been his subjects. With “Klara and the Sun,” I began to see how he has mastered the adjacent theme of obsolescence. What is it like to inhabit a world whose mores and ideas have passed you by? What happens to the people who must be cast aside in order for others to move forward? The climax of “The Remains of the Day” (1989), Ishiguro’s perfect, Booker Prize-winning novel, pivots on a butler’s realization that his whole life has been wasted in service of a Nazi sympathizer. (“I gave my best to Lord Darlington. I gave him the very best I had to give and now — well — I find I do not have a great deal more left to give.”) A subplot in Ishiguro’s first novel, “A Pale View of Hills” (1982), involves an older teacher in postwar Nagasaki whose former student renounces his way of thinking. “I don’t doubt you were sincere and hard working,” the former student tells him. “I’ve never questioned that for one moment. But it just so happens that your energies were spent in a misguided direction, an evil direction.” In “Never Let Me Go,” clones “complete” after fulfilling their biological purpose. In “Klara and the Sun,” obsolescence reaches its mass conclusion: Whole classes of workers have been replaced by machines, which themselves are subject to replacement. It nearly happens to Klara. In the story’s first section, a new, improved model of AF arrives and bumps her to the back of the store.

Klara’s Eye

Klara and the Sun” lands in a pandemic world, in which vaccines hold the promise of salvation but the reality of thousands of deaths a day persists, and a substantial portion of the American population deludes itself into thinking it isn’t happening. Our own children have been learning on oblongs and in isolation. The crisis of this novel revolves around whether Josie, with Klara’s help, will recover from her illness — and whether, if Josie doesn’t recover, her mother, with Klara’s help, will survive the loss. It turns out that to “lift” her daughter, to ensure Josie will thrive amid her world’s “savage meritocracies” (I’m quoting from Ishiguro’s 2017 Nobel lecture, an enlightening document as to his state of mind), her mother has knowingly risked Josie’s health, her happiness, her very life — a calculation that sounds terrible on paper until one realizes how common it already is.

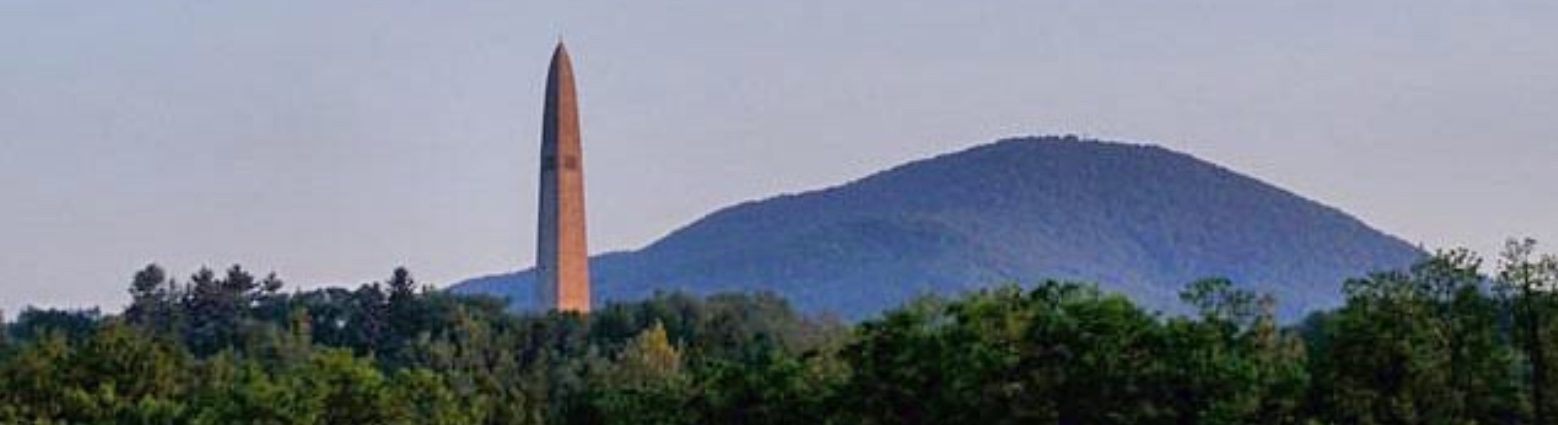

Considering the place of “Klara and the Sun” in Ishiguro’s collected works — which cohere astoundingly well, even “The Unconsoled” (1995), powered as it is by the dreamlike absorption and reconciliation of unfamiliar circumstances — I found myself thinking of Thomas Hardy, the way Hardy’s novels, at the end of the 19th century, captured the growing schism between the natural world and the industrialized one, the unclean break that technology makes with the past. Tess Durbeyfield earns her living as a dairymaid before agricultural mechanization, but she channels early strains of what Hardy presciently calls “the ache of modernism.” She represents a mode of being human in nature before machinery got in the way.

Read Other Reviews:

The New Scientist : Klara and the Sun review: Ishiguro’s thought-provoking future for AI

The Atlantic: The Radiant Inner Life of a Robot

The New Republic : Kazuo Ishiguro’s Deceptively Simple Story of AI

Read About Artificial Intelligence

Can a Machine Know That We Know What It Knows?

Return to Table of Contents