by Gudrun Hutchins

Sojourner Truth was a nationally known advocate for justice and equality between races and sexes during the 19th century. She is honored in American history for innumerable speeches against slavery and for women’s rights, for her work on behalf of freedmen after the Civil War, for her ability to keep audiences enthralled with her songs and speeches, and for the compelling Narrative of the first 50 years of her life that she dictated to Olive Gilbert.

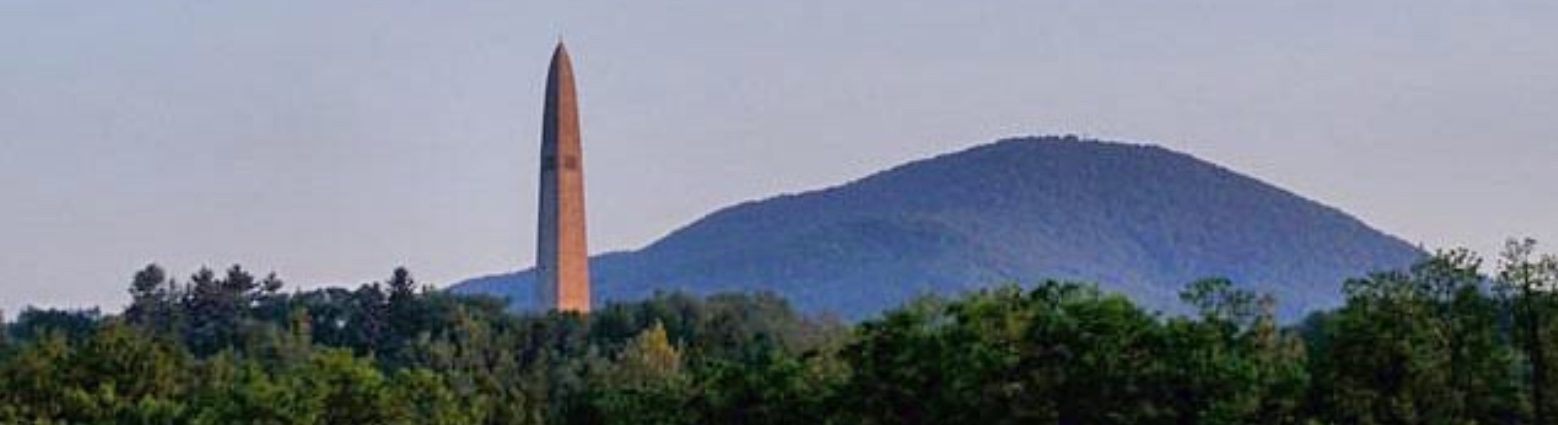

Sojourner Truth was given the name Isabella (“Belle”) Baumfree at birth. She was born near Roundout Creek in the town of Hurley, Ulster County, New York. Although her exact birth date is unknown, it is believed that she was born around 1797 on the estate of Colonel Johannis Hardenbergh. The area no longer carries any physical evidence of Belle’s birthplace, but a plaque in her honor commemorates the probable location.

Colonel Johannis Hardenbergh owned six adult slaves on his estate. At the time of Belle’s birth, her family lived in a small cottage surrounded by farmland on which they could cultivate crops to sell for “extras” that were not supplied by their master. Shortly after Belle’s birth, Colonel Hardenbergh died and his son Charles inherited the estate. Charles moved Truth’s parents and children from their cottage and they lived and slept in the dark cellar of the main house with the rest of his slaves.

As the youngest of at least ten children, Belle’s early life was marked with swift transitions as many of her older siblings were sold. After Charles Hardenbergh died in 1806, nine-year-old Belle was sold at an auction together with a flock of sheep for $100 to John Neely, who lived near Kingston, New York. In 1808 Neely sold Belle for $105 to fisherman and tavern keeper Martinus Schryver of Port Ewen, New York, who owned her for 18 months. Schryver then sold Belle to her last master John Dumont of West Park, New York who owned her until she was 30 years old.

At the turn of the nineteenth century, enslaved Africans living in rural areas of New York State were often Afro-Dutch. This was true of Belle and her family, and her first language was Dutch. When Truth was sold to John Neely, he and his family only spoke English. Truth recalled being brutally beaten for not understanding their English demands. Over her lifetime, Truth learned to speak English fluently but never lost her Dutch accent or learned how to read and write.

John Dumont was a fairly humane master, but also a rapist. As a result, considerable tension existed between Belle and Dumont’s wife, who harassed her and made her life more difficult. Dumont was the father of Belle’s oldest daughter Diana who was born when Belle was 18. Diana lived with Dumont, her father, into his old age long after all slaves in New York had been freed by New York State law. Dumont may have also have been the father of Belle’s oldest child James, who died in early childhood.

While enslaved by her last master John Dumont, Belle fell in love with an enslaved man named Robert from a neighboring farm. His masters, the Catlins, did not want Robert to have children that they could not benefit from and forbade the relationship. In her dictated Narrative, Truth recalls Robert sneaking to Dumont’s farm to visit her when she was ill. The Catlins found him and they “fell upon him like tigers,” tying his hands and severely beating him until Dumont intervened. After this, a somber Robert married a woman from the Catlin farm and Truth was married to Thomas, an older man from the Dumont farm whose previous two wives had been sold. Robert and Belle had three children.

In 1799, the State of New York began to legislate the abolition of slavery, although the process of emancipating people enslaved in New York was not completed until July 4, 1827. Dumont had promised to grant Belle her freedom a year before the state emancipation, “if she would do well and be faithful.” However, he changed his mind, claiming that a hand injury had made her less productive. She was infuriated but continued working, spinning 100 pounds of wool, to satisfy her sense of obligation to him.

Late in 1826, Belle escaped to freedom with her infant daughter, Sophia. She had to leave her other children behind because they were not legally freed by New York’s emancipation order until they had served as bound servants into their twenties. Although Dumont pursued her, she was able to stay with Isaac and Maria Van Wagenen in New Paltz. Isaac offered to buy her services until the emancipation law took effect, which Dumont accepted for $20.

Truth had a life-changing experience during her stay with the Van Wagenens and became a devout Christian. She moved to New York City in 1829, where she worked as a housekeeper for Elijah Pierson, a Christian Evangelist. In 1832 she met Robert Matthews, also known as Prophet Matthias and went to work for him as a housekeeper at the Matthias Kingdom communal colony. Elijah Pierson died, and Robert Mathews and Belle Baumfree were accused of stealing from and poisoning him. Both were acquitted of the murder, but Mathews was convicted of lesser crimes, served time, and moved west.

The year 1843 was a turning point for Baumfree. She became a Methodist, and on June 1, Pentecost Sunday, she changed her name to Sojourner Truth. She chose the name because she heard the Spirit of God calling on her to preach the truth. She told her friends: “The Spirit calls me, and I must go”, and left to make her way traveling and preaching about the abolition of slavery. Taking along only a few possessions in a pillowcase, she traveled north, working her way up through the Connecticut River Valley toward Massachusetts.

At that time, Truth began attending Millerite Adventist camp meetings. Millerites followed the teachings of William Miller of New York, who preached that Jesus would appear in 1843-1844, bringing about the end of the world. Many in the Millerite community greatly appreciated Truth’s preaching and singing and she drew large crowds when she spoke. Disappointed when the anticipated second coming did not arrive, Truth distanced herself from her Millerite friends for a time.

In 1844 Truth joined the Northampton Association of Education and Industry in Florence, Massachusetts. Founded by abolitionists, the organization supported women’s rights and religious tolerance as well as pacifism. In its 4 ½ year history, there were a total of 240 members with about half living there at any one time. They raised livestock, ran a sawmill, a gristmill, and a silk factory. A number of the houses were stops in the Underground Rail Road. Truth lived and worked in the community and oversaw the laundry, supervising both men and women. While there, Truth met William Lloyd Garrison, Frederick Douglass and David Ruggles. Encouraged by the community, Truth delivered her first antislavery speech that year.

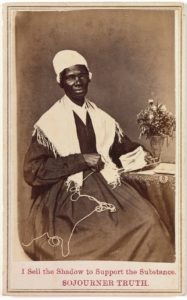

Truth started dictating her memoir to her friend Olive Gilbert and in 1850 William Lloyd Garrison privately published the book. In the same year she purchased a home in Florence for $300 and spoke at the first National Women’s Rights Convention in Worcester. In 1854 she paid off the mortgage for the home from sales of the Narrative and visiting cards with her photograph.

Her words at the Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio in 1851 exist in two versions that are vastly different. One was transcribed by her friend Rev. Marius Robinson, a newspaper owner and editor who was in the audience. He discussed his transcription with Truth after her speech and she presumably approved his transcription before he published it in his newspaper, the Salem (Ohio) Antislavery Bugle three weeks after the Conference. The issue of the newspaper is in the Collection of the Library of Congress and this is Robinson’s text:

“Women’s Rights Convention

Sojourner Truth

One of the most unique and interesting speeches of the Convention was made by Sojourner Truth, an emancipated slave. It is impossible to transfer it to paper, or convey any adequate idea of the effect it produced upon the audience. Those only can appreciate it who saw her powerful form, her whole-souled earnest gestures, and listened to her strong and truthful tones. She came forward to the platform and addressing the President said with great simplicity:

May I say a few words? Receiving an affirmative answer, she proceeded.

I want to say a few words about this matter. I am a woman’s rights. I have as much muscle as any man, and I can do as much work as any man. I have plowed and reaped and husked and chopped and mowed, and can any man do more than that? I have heard much about the sexes being equal, I can carry as much as any man, and can eat as much too, if I can get it. I am as strong as any man that is now. As for intellect, all I can say is, if woman have a pint and man a quart – why can’t she have her little pint full? You need not be afraid to give us our rights for fear we will take too much, — for we can’t take more than our pint’ll hold. The poor men seem to be all in confusion, and don’t know what to do. Why children, if you have woman’s rights, give it to her and you will feel better. You will have your own rights, and they won’t be so much trouble. I can’t read, but I can hear. I have heard the Bible and have learned that Eve caused man to sin. Well if woman upset the world, do give her a chance to set it right side up again. The Lady has spoken about Jesus, how he never spurned woman from him, and she was right. When Lazarus died, Mary and Martha wept – and Lazarus came forth. And how came Jesus into the World? Through God who created him and woman who bore him. Man, where is your part? But the women are coming up, blessed be God, and a few of the men are coming up with them. But man is in a tight place, the poor slave is on him, woman is coming on him, and he is surely between a hawk and a buzzard.”

The second version was written by Frances Gage, one of the organizers of the 1851 Convention 12 years later during the middle of the Civil War. It is twice as long and is written in the heavy accent of a southern slave in a minstrel like fashion with the refrain “Ain’t I a Woman” repeated four times during the speech. These are speech patterns that Truth did not possess. Gage’s version also included major factual errors such as Truth saying her 13 children were sold away from her into slavery. Truth is widely believed to have had five children. Only one of her children was sold, but she won a court case against the white owner and her son was released into her custody. The “Ain’t I a Woman” phrase may not have been a total invention, but she did not use it at the 1851 conference. She was nearly six foot tall and of strong build and was accused of being a man on several occasions. During one speech she opened her blouse and showed her breasts to prove that she was a woman. Unfortunately, it is Gage’s inaccurate version published during the middle of the Civil War that has entered the literature.

In September 1857, she sold all of her possessions and moved to Battle Creek, Michigan, where she rejoined former members of the Millerite movement who had formed the Seventh Day Adventist Church. From 1857 to 1867 Truth lived in the village of Harmonia, Michigan, a Spiritualist utopia.

During the Civil War, Truth helped to recruit black troops for the Union Army. Her grandson, James Caldwell, enlisted in the 54th Massachusetts Regiment. In 1863, she went door to door to collect Thanksgiving food for the First Michigan Regiment of Colored Soldiers in Detroit.

In 1984, Truth was employed by the National Freedman’s Relief Association in Washington D.C., where she worked diligently to improve conditions for African-Americans. She fought for issues such as the resettlement of freed people in the west, where they would receive “forty acres and a mule.” On October 29th of that year, Truth met President Abraham Lincoln in the White House. In 1865, while working at the Freedman’s Hospital in Washington, Truth rode in the streetcars to help force their desegregation.

Sojourner Truth died of old age in Battle Creek, Michigan, on November 26, 1883 at the age of approximately 86. Since her death, Truth’s likeness can be found on paintings, statues, and within the pages of history textbooks.

To learn more:

Truth, Sojourner, and Olive Gilbert Narrative of Sojourner Truth, a Northern Slave, Emancipated from Bodily Servitude by the State of New York, in 1828

Electronic edition of the book in the Library of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. This is a very long but fascinating document that covers the first 52 years of her life. It is not an autobiography or journal in the usual sense. Olive Gilbert used Truth’s dictated material to create a third person biography that is also an anti-slavery treatise. In a number of places Gilbert has inserted a paragraph that points out that what has happened to “our heroine” illustrates one of the terrible aspects of slavery.

An Educational Website about Florence, Massachusetts including a digital walk through the historic village. The walk can also be completed in person during a visit.

An analysis of the two speeches from the 1851 Civil Rights Conference in Akron Ohio. The website includes recording of the speech published by Marius Robinson read by women with an African-Dutch accent to see how it might have sounded.

National Women’s History Museum slide show about Sojourner Truth’s life.

Return to Table of Contents