By Gudrun Hutchins

Shortly after Ellen Henrietta Swallow married MIT mining professor Robert Hallowell Richards in June 1875, the couple set off for a honeymoon in Nova Scotia. They had fallen in love when Ellen was a chemistry student at MIT, and after she graduated with a bachelor’s degree in 1873, Robert proposed to her in the laboratory. Upon their return from Canada, the newlyweds – Ellen still wearing a short (above the heel!) skirt and high boots – bumped into some friends in Boston and thoroughly shocked them. The happy couple revealed that they had spent their entire honeymoon touring mines and collecting ore samples, with several of Professor Richards’s mining-engineering students in tow.

Given all that she accomplished in her 68 years, it’s no surprise that the Richards’s honeymoon doubled as a geology field trip. As a student at Vassar (from which she graduated before attending MIT) she didn’t waste a minute: she earned a reputation for knitting as she climbed the five flights of stairs to her dorm room, and for reading as she walked to class. She loved science, particularly astronomy and chemistry, and took every science class Vassar offered except one. Although she excelled in astronomy (she even found star clusters her teacher couldn’t identify) and called the telescope “an entrancing instrument,” she pursued chemistry because its potential practical applications appealed to what she would later recognize as her inclination toward social service.

That inclination would grow into a passion. At 23, she wrote to her cousin, “Pray for me, dear Annie, that my life may not be entirely in vain, that I may be of some use in this sinful world.” Her life would be useful indeed, as she applied her scientific expertise to a dizzying array of public-service initiatives that would make science education accessible to women, improve public health and the environment, and promote health and efficiency in the home.

Opening Doors

On her last day at Vassar, in June 1870, Ellen Swallow wrote a prophetic letter to her parents in which she declared, “My life is to be one of active fighting.” She wasn’t sure what she would do next, since few professions other than teaching were open to women. But Swallow did know that she longed to deepen her knowledge of chemistry, and that she wanted to help expand women’s boundaries. Before she could open doors for others, however, she had to pry them ajar for herself.

Ellen Swallow at the time of her graduation from Vassar

Her options were limited. Science schools admitted only men at that time, and she couldn’t learn any more at the few colleges then open to women than she already had at Vassar. Four months after graduation, Swallow wrote to a Boston chemical company asking if it would take her on as an apprentice. The company declined and recommended that she try the new Institute of Technology in Boston.

Although MIT president J. D. Runkle wrote to her that allowing women at the Institute was “a consummation devoutly to be wished,” some on the faculty weren’t so sure. But after discussing her application, they recommended her acceptance to the Corporation, which decided to offer her free admission as a special student of chemistry.

As she would be the first woman to infiltrate the Institute, her admission was couched as an experiment; her tuition was waived, she later learned, so President Runkle could say that she wasn’t a student if any trustees or students objected. It also freed MIT from any obligation should the experiment fail.

Determined to succeed, Swallow eagerly learned as much as she could about chemistry, physics, and mineralogy, all the while being careful to “roil no waters,” as she put it. “I hope that I am winning a way which others will keep open,” she wrote shortly after her arrival in January of 1871. She kept the lab clean and mended one professor’s suspenders in an effort to be “useful” and to show that she didn’t reject woman’s sphere. Soon she won over even the most skeptical professor, William Ripley Nichols, with her careful lab work, exceptional intelligence, and humble, unthreatening manner. In 1872 Nichols, who had not believed in women’s education, selected her to conduct a groundbreaking survey of Massachusetts waters; her work on the project made her an internationally recognized water scientist while still a student.

Swallow graduated from MIT in 1873 with a Bachelor of Science degree. She continued to produce enough outstanding work to be eligible for an advanced degree; however, President Runkle had decided that the honor of the first doctorate from MIT should be reserved for a male. While analyzing iron ore samples from various locations within the United States, Ellen had developed new methods for determining their nickel and arsenic concentrations. (Nickel is a more valuable metal than iron and arsenic poses a potential danger to miners.) During the process Ellen discovered and isolated two new chemical elements.

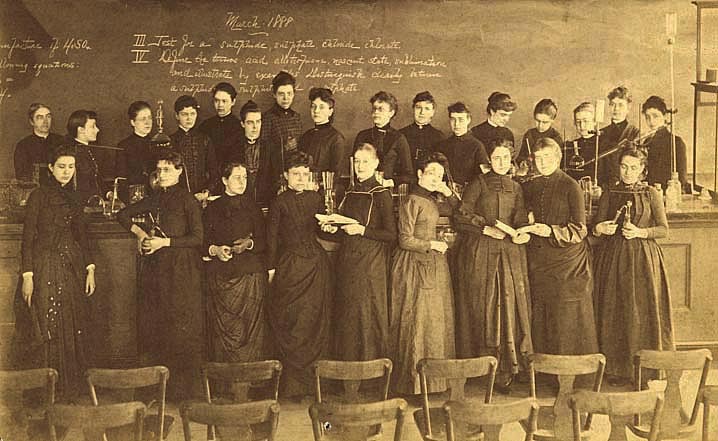

After graduation, Swallow labored tirelessly on behalf of women seeking a science education. She persuaded MIT to provide the space for a Women’s Laboratory on the MIT campus and asked the Boston-based Women’s Education Association (WEA) to provide money for equipment and chemicals. The Women’s Laboratory opened in 1876 and about 500 women – many of them secondary-school teachers without access to laboratories – studied chemistry under Mrs. Richards (as by then she was known). To those who were strapped financially, Richards offered room and board at her Jamaica Plains home in exchange for housework. Ultimately, the laboratory became obsolete since MIT built a new chemistry lab for both men and women in 1883.

Ellen Swallow Richards and a group of her students in the Women’s Laboratory at MIT. Ellen herself is standing at the left side of the back row.

Richards also taught thousands of women who couldn’t attend MIT. In 1876 she began managing the science section of the Society to Encourage Study at Home, a correspondence school intended to, as the catalogue put it, “induce ladies to form the habit of devoting some part of every day to study of a systematic kind.” Undaunted by the logistical challenge of teaching an inherently hands-on subject by mail, Richards sent her students microscopes, specimens, texts, and lessons. She urged women to examine anything that interested them – plants, food, or water from the well, for example. For some, the experience was life changing. One student wrote, “I have eyes to see what I never saw before.”

Founding AAUW and Continuing to Open Doors for Women

Not all of Richards’s initiatives to advance women involved teaching. To lend support to women seeking higher education, she co-founded the Association of Collegiate Alumnae together with her student Marion Talbot. An exploratory meeting was held with 15 alumnae in Marion Talbot’s Boston home in December 1881. The charter meeting took place in an MIT lecture hall in January 1882 and was attended by 65 alumnae of a number of different colleges. After merging with two additional regional alumnae associations, the organization became known as the American Association of University Women. The organization provided fellowships and worked to raise the standard of women’s scholarship at the college level. Ellen Richards remained an active member of AAUW for the rest of her life.

Richards once again enlisted the help of the WEA to bankroll a laboratory that would allow women (and men) to do research in the field of marine biology, then undeveloped in the United States. The Summer Seaside Laboratory opened in the summer of 1881 in Annisquam, MA. Six years later, the facility was moved to Woods Hole, where it remains today.

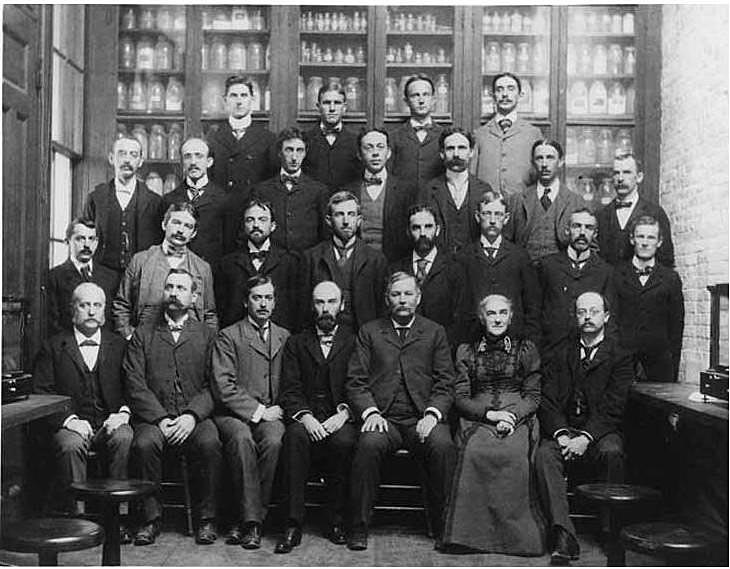

In 1884, shortly after the Women’s Laboratory closed, the Institute appointed Ellen Swallow Richards as instructor in a new discipline called “sanitary chemistry and engineering.” It was her first paid position at MIT and she held it until her death in 1911. Nominally she still worked under the “supervision” of a professor because she did not have the earned doctorate degree that the MIT Corporation would not award to a woman. However, the MIT faculty considered her their equal as is indicated in a historic photo of the chemistry staff taken in 1900.

MIT Chemistry Faculty in 1900

From 1884 to her death in 1911, she taught sanitary chemistry, sanitary engineering, and air, water, and food analysis to countless MIT students, many of whom became leaders in public sanitation in the United States and abroad.

Her writings reached many more people. Richards wrote or coauthored 18 books – from academic texts in sanitary engineering to practical manuals for housewives on the chemistry of cooking and cleaning as well as scores of papers and articles. She felt that a basic knowledge of scientific principles could improve people’s lives. A housewife who knew some simple chemistry could test the purity of household products like cream of tartar or tea if she suspected they had been adulterated. If she understood nutrition, ventilation, and plumbing, she could provide the healthiest possible environment for her family. Richards founded the popular American Kitchen Magazine, which brought science into housewives’ hands, and was the “guiding spirit” behind the scholarly Journal of Home Economics.

Her scientific achievements were remarkable not only for how groundbreaking many of them were, but also for the diversity of fields she contributed to: air quality, mineralogy, industrial chemistry, food and consumer sciences, and water quality. In the last two areas, her work sparked some of the country’s first public-health standards and regulations. Students from the Women’s Lab helped her conduct research on nutrition, consumer products, and food adulteration, both in the lab at MIT and in her kitchen in Jamaica Plains – the nation’s first consumer-products test lab. At the time, there were no laws regulating the quality of food. In 1878 and 1879, Richards and her students conducted a study for the Massachusetts Board of Health, Lunacy, and Charity on adulteration of staple foods, the first such study in the nation. The results of this and further research were alarming: watered-down milk; samples of cinnamon that consisted entirely of mahogany sawdust; salt and sand in sugar; and sauces with tainted meat, to name a few discoveries. Their findings prompted the state to pass the first of its Food and Drug Acts in 1882.

Even in her final years, Richards hardly slowed down. She consulted for some 200 organizations and continued to teach, conduct research, travel, and write prodigiously. Despite a worsening shortness of breath, she persisted in climbing three long flights of stairs to reach her MIT office, refusing to take the elevator. But her ailing heart caught up with her on March 30, 1911. Fittingly, on the day her funeral was reported in the newspapers, so too was the news that five companies had been indicted for violating the new food and drug laws.

Richards would probably have wished to do more, but even she might concede, on balance, that her life had been “useful.” She often closed her letters with two simple words: “Keep thinking.” And in her extraordinary career, she inspired countless other people–women and men from all walks of life–to do just that.

(Some of the historical information was obtained from the AMITA exhibit “125 Years of MIT Women.” Although the admission of Ellen Swallow to MIT was “an experiment,” the corporation is now very proud of the accomplishments of their first alumna. (AMITA is the Association of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Alumni.)