by Gudrun Hutchins

Ida B. Wells was born on July 16, 1862 in Holly Springs, Mississippi. She was born into slavery during the second year of the Civil War as the first child of James Madison Wells and Elizabeth Warrenton. Ida’s grandfather was James’ white owner who had impregnated an enslaved black woman named Peggy. Before his death James’ father had apprenticed his 18-year-old son to Spires Bolling, an architect and builder. Ida’s father became a skilled building craftsman and helped to repair and rebuild Holly Springs after the war.

After the Emancipation Declaration was signed, Ida’s parents quickly exercised the privileges of freedom. They legalized their marriage, and as their family grew they deepened their commitment to education as a way out of poverty. Ida later wrote, “Our job was to go to school and learn all we could.” Ida enrolled in the historically black Rust College but was expelled after two years when she started a dispute with the college president.

In 1878 tragedy struck the family. While Ida was visiting her grandmother’s farm, a yellow fever epidemic hit her hometown and both of her parents and her youngest brother died of the disease. To keep her younger siblings together as a family, she found work as a teacher in a black elementary school in Holly Springs. Her paternal grandmother Peggy Wells, along with other friends and relatives, cared for her siblings during the week while Wells was teaching. But after Peggy Wells died from a stroke, Wells accepted the invitation of her aunt Fanny and moved with her two youngest sisters to Memphis in 1883.

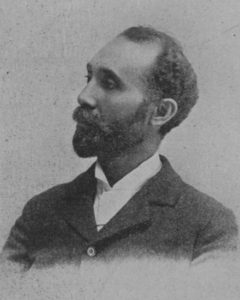

Ida B. Wells in 1893. Age 31.

While she waited to take the examination for teaching in the public schools of Memphis, Wells accepted a job in Woodstock, a rural community outside of Memphis. During her summer vacations she attended summer sessions at Fisk University in Nashville, she also attended Lemoyne-Owen College in Memphis.

An important incident occurred on a train trip from Memphis to Woodstock. Eighty years before Rosa Parks refused to move to the back of a bus in Montgomery, Alabama, twenty-two-year-old Wells refuse to move out of her train seat for which she had paid. She had bought a ticket for the first-class ladies’ car and refused the conductor’s order to move to the smoking car, which was already crowded with other passengers. The authorities forcibly removed her from the train. Backed by the Civil Rights Act of 1875, she filed and won a lawsuit against the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad and was awarded $500 in damages. However, the Tennessee Supreme Court shortly reversed the victory. Frustrated, she began writing political columns in church newspapers. Having secured a job in the Memphis public schools, she saved her money and became part owner of a small newspaper called Free Speech and Headlight in Memphis.

In 1891, Wells was dismissed from her teaching post by the Memphis Board of Education due to her articles that criticized conditions in the black schools of the region. She was devastated but undaunted, and concentrated her energy on writing articles for The Living Way and the Free Speech and Headlight.

In 1889, a black proprietor named Thomas Moss opened the People’s Grocery in a South Memphis neighborhood. Wells was close to Moss and his family, having stood as godmother to his first child. Moss’s store did well and competed with a white-owned grocery store across the street. Moss and two friends defended their small grocery against six white men who attempted to put them out of business. After a deputy sheriff was wounded during the confrontation, all three black men were arrested. At 2:30 am 75 men wearing black masks took Moss and his two friends from their jail cells to a rail yard one mile north of the city and shot them.

The event led Wells to begin investigating lynchings using investigative journalist techniques. She began to interview people associated with lynchings, including a lynching in Tunica, Mississippi in 1892, where she concluded that the father of a young white woman had implored a lynch mob to kill a black man with whom his daughter was having a sexual relationship, to “save the reputation of his daughter.”

On May 21, 1892, Wells published an editorial in the Free Speech refuting what she called “that old threadbare lie that Negro men rape white women.” Four days later, The Daily Commercial published “The fact that a black scoundrel is allowed to live and utter such loathsome and repulsive calumnies is a volume of evidence as to the patience of Southern Whites. But we’ve had enough of it.” A white mob ransacked the Free Speech office, destroying the building and its contents. The trains were being watched for Ida’s return. She had been vacationing in New York and never returned to Memphis.

Wells joined the staff of the New York Age and lived in Harlem as the guest of a supporter. In 1893, she moved to Chicago and attacked the exclusion of black people from the Chicago World’s Fair, writing a pamphlet sponsored by Frederick Douglas and others. She travelled twice to England on lecture tours and was well received there. She and her supporters saw these tours as an opportunity for her to reach larger, white audiences with her anti-lynching campaign, something she had been unable to accomplish in America. In Britain, she found sympathetic audiences, already shocked by reports of lynching in America. She began to work tirelessly against segregation and for women’s suffrage and helped block the establishment of segregated schools in Chicago.

Lynching Pamphlet

In June 1895 (at age 33), Wells married attorney Ferdinand L. Barnett, a widower with two sons. A prominent attorney, Barnett was a civil rights activist and journalist. Barnett had founded The Chicago Conservator, the first black newspaper in Chicago in 1878. Wells began writing for the paper in 1893, later acquired a partial ownership interest, and after marrying Barnett, assumed the role of editor.

Attorney Ferdinand Lee Barnett

Wells’ marriage to Barnett was a legal union as well as a partnership of ideas and actions. Both were journalists, and both were established activists with a shared commitment to civil rights. This sort of close working relationship between a wife and husband was unusual at the time, as women generally played more traditional domestic roles in a marriage. After her marriage Wells published her articles as Ida B. Wells-Barnett or under her pen name Iola.

In addition to Barnett’s two children from his previous marriage, the couple had four additional children. In the chapter of her Crusade for Justice autobiography called “A Divided Duty,” Wells described the difficulty she had splitting her time between her family and her work.

Ida B. Wells with her Children–Age 41

Wells-Barnett focused her work on black women’s suffrage in Chicago following the enactment of a new state law enabling partial women’s suffrage. It gave women the right to vote for presidential electors, mayor, aldermen and most other local offices, but not for governor, state representatives, or members of Congress.

This act was the impetus for Wells-Barnett and her white colleague Belle Squire to organize the Alpha Suffrage Club in Chicago in 1913. The important suffrage organization was founded as a way to further voting rights for all women, to teach black women how to engage in civic matters and to work to elect African Americans to city offices.

While Wells-Barnett and Squire were organizing the Alpha Club, the National American Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was organizing a suffrage parade in Washington D.C. Marching the day before the inauguration of Woodrow Wilson in 1913, suffragists from across the country gathered to demand universal suffrage. Wells-Barnette, together with a delegation of members from Chicago, attended. On the day of the march, the head of the Illinois delegation told the Wells delegates that the NAWSA wanted “to keep the delegation entirely white.” All African-American suffragists, including Wells were to walk at the end of the parade in a “colored delegation.” Instead of going to the back with other African Americans, however, Wells waited with spectators as the parade was underway, and stepped into the white Illinois delegation as they passed by. Wells visibly linked arms with her white suffragist colleagues, Belle Squire and Virginia Brooks for the rest of the parade, demonstrating, according to the Chicago Defender, the “universality of the women’s civil rights movement.”

To learn more:

Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells – The unfinished autobiography was edited and published by her daughter Alfreda Barnett Duster 40 years after Ida’s death.

To Keep the Waters Troubled: The Life of Ida B. Wells by Linda O. McMurry

A Passion for Justice Film on YouTube: https://youtu.be/7NUyPFAJE9M

Return to Table of Contents