By Gudrun Hutchins

In 2009, Aileen Rizo, a long time math teacher, relocated with her husband and two young daughters, ages 1 and 4, from Arizona to California to take a job in Fresno County as a math consultant, training other math teachers in several school systems.

In the summer of 2012, Rizo was wrapping up a lunch meeting at the Fresno County Office of Education when she overheard something that horrified her. As she gathered her papers, three men in her department started casually discussing their salaries. “Hey,” said a guy who had just been hired, “I just signed my contract and I got Step 9 (roughly $79,100).” As the other men congratulated him, Rizo quietly fumed. Step 9? In the office hierarchy, Step 9 was near the top of the compensation ladder nearly $17,000 more than her Step 1 starting salary of $62,133. Moreover, she had two master’s degrees (he had none) and more years of teaching experience. He didn’t even have a math degree! “I didn’t completely know what my rights were,” says Rizo, “but I knew it was wrong.”

She and her family had just moved into a new house, and as the primary breadwinner, the last thing she wanted to do was to rock the boat. But she expected the pay issue to be quickly rectified. “In my mind, I thought this was going to be a sprint race; this is black and white, and eventually someone’s going to realize they just need to make this right.”

“When I came home that day, my two daughters ran into my arms and it hit me like never before: What I choose to do – or not do – will impact my girls. I want them to grow up in a world where they are treated equally.”

Human resources informed Rizo that they had used a formula to calculate her starting salary: They looked at what she earned from her last employer and added 5 percent. Rizo, who grew up in a relatively poor neighborhood in South Phoenix and was the first in her family to go to college, was livid at the injustice. I told her, “That doesn’t take into account my education, my experience!” And she said, “Well, that’s the way we’ve always done it.”

Rizzo, who had spent the past weekend brushing up on the Equal Pay Act, promptly recited her rights: “You have to pay a man and a woman the same amount of money for the same work. When I said that, she picked up a notepad, jotted a few things down, and told me she was going to investigate it and would get back to me the next week.

One week turned into three, and eventually human resources stopped communicating with her. At that point Rizo hired a lawyer with experience in gender discrimination.

Rizo filed suit in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of California in 2014 under the 1963 Federal Equal Pay Act and California Sex Discrimination statutes. Rizo’s first ray of hope came in 2014, when the district court judge denied the county office’s attempt to have the case dismissed. However, there was an additional factor that AAUW never reported but that is clear from the superintendent’s deposition and from court arguments. Another woman had held a similar job with the county two years before Rizo arrived and she was hired at step 8 based on her prior salary. Therefore, the case could not be argued on the basis of gender discrimination, but only on the basis that salary history alone was not a valid basis for determining the salary of a new employee.

Part of the challenge as a plaintiff is signing on not only oneself but also loved ones for a potentially grueling ordeal. Rizo’s husband has supported her from the beginning. But she feels guilty about the toll this has taken on her daughters, especially during the first years of the case while Rizo was still working for the county. “They probably deserved a mother who was much happier at the time.” Rizo’s youngest daughter understands little about the trial, but her short life has revolved around it – she was only six weeks old at the time of Rizo’s first Ninth Circuit deposition in San Francisco. She remembers thinking: “I could be home on maternity leave, and I’m here doing a deposition… but I have to fight for equal pay to support my family.”

The guilt and unhappiness were intense, but she also felt pressure to stay the course to be a role model for girls in the schools. As the only woman and the only racial minority (she is Latina) in a department of five full-time workers, she stood out in classrooms to coach teachers. “These freshmen girls would see a woman who looked like them and they would say, ‘Wow, she’s my teacher’s math teacher!’ And I felt that was powerful – that I should not give that up because I couldn’t get through a rough spot in my career.”

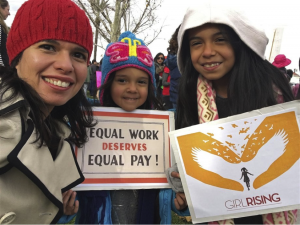

Aileen Rizo with two of her daughters at the Women’s March in Fresno California on January 21, 2017.

Fresno County appealed the District Court’s favorable decision to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals which covers the west coast of the United States and some of the adjacent states. But the hearing did not unfold as Rizo had anticipated. An Equal Employment Opportunity Commission representative testified on Rizo’s behalf, but a three judge panel of the Ninth Circuit overturned the lower court decision in April 2016, ruling that Rizo’s employer had not violated the Equal Pay Act because he had a “legitimate business purpose” for establishing pay using salary history alone. Rizo says: “I was just floored that this was allowed.”

Support from AAUW members has been crucial for Rizo’s morale. Her husband was the first to hear about AAUW; it was Equal Pay Day and he texted his wife about an event at the local AAUW Fresno County Branch. She went and met the members there, shared her story, started attending meetings, and eventually joined the organization. She also began testifying in support of California equal pay bills, which led to locals inviting her to share her story.

At her first court hearing Rizo remembers the moment she started to feel anxious about what was coming, and then she looked around the room and received a boost of confidence. “There was a courtroom full of AAUW women I had never met before; they had heard about my case and came to support me…. There are many times on this journey when you feel alone. To have women I had never met before sayingm ‘I’m with you,’ that was really encouraging.”

After the three judge panel from the Ninth Circuit Court had ruled against her, the only option for Rizo was to request an “en banc” (full court) hearing from the Ninth Circuit Court claiming that the three judge panel had made a mistake. AAUW worked with a consortium of organizations headquartered in Washington to prepare a new legal brief. National AAUW and AAUW of California signed on as amicus curiae (friend of the court) along with 15 other organizations.

The United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit comprises 29 active judgeships. Requests for en banc hearings are fairly common, but the number that is actually heard is very small. Each year the Ninth Circuit receives about 1,500 requests for rehearings en banc, but only 15 – 25 are heard. Rizo’s hearing began on December 11, 2017 with oral arguments. This time Rizo was as successful as she had hoped. The eleven judges of the en banc court unanimously ruled in Rizo’s favor. A large number of legal and lay publications hailed the decision as important and precedent-setting. What follows is a small part of the story published in US News:

SAN FRANCISCO — Relying on a woman’s previous salary to determine

her pay for a new job perpetuates disparities in the wages of men and women and is illegal when it results in higher pay for men, a federal appeals court ruled Monday. The unanimous ruling by an 11-judge panel of the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals came in a lawsuit filed by a California school employee who learned over lunch with colleagues in 2012 that she made thousands of dollars less than her male counterparts. The 9th Circuit held that pay differences based on prior salaries are inherently discriminatory under the federal Equal Pay Act because the previous salaries were the result of gender bias.

“Women are told they are not worth as much as men,” Judge Stephen Reinhardt wrote before he died last month. “Allowing prior salary to justify a wage differential perpetuates this message, entrenching in salary systems an obvious means of discrimination.”

The policy was “gender-neutral, objective and effective in attracting qualified applicants,” Fresno County Superintendent of Schools Jim Yovino responded in a statement Monday, saying he will appeal the ruling to the U.S. Supreme Court. The policy was applied to more than 3,000 employees over 17 years and had “no disparate impact on

female employees.”

The Supreme Court remanded (sent back for reconsideration) the ruling to the Ninth Circuit Court on a technicality. Judge Reinhardt, who had authored the ruling, died before the decision was officially filed. This made the ruling invalid, even though all the votes had been taken before his death. As Chief Justice Roberts pointed out “Judges are appointed for life, but not for eternity.”

The U. S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals held another en banc hearing as instructed by the Supreme Court. Since some of the judges assigned to the case were not the same, the case had to be re-argued, but they did so without requiring new oral arguments from Rizo and her lawyers. The ruling was properly filed and sent back to the Supreme Court. In July, the Supreme Court declined to hear it. So the decision stands for all residents of the states and territories encompassed by the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

What is Aileen Rizo doing now? After testifying several times for California Pay Equity Laws, Aileen ran for the California State Assembly from the 23rd district in 2018. She won the Democratic Primary, but lost to the Republican incumbent with many connections and more funding. Asked why she sought to represent her district, she replied: “He vetoed all the equal pay legislation for which I testified.”

Aileen Rizo currently serves as the Associate Director of the AIMS Center for Math and Science Education, a non-profit that is located on the campus of Fresno Pacific University. She works with several school systems to introduce new ways of teaching math and science to gifted students and to racial minorities. Now and then, she still has opportunities to coach teachers in their classrooms.